One Way to Help Prevent Mass Murder in a Federal Workplace

By William Wiley, April 17, 2023

By William Wiley, April 17, 2023

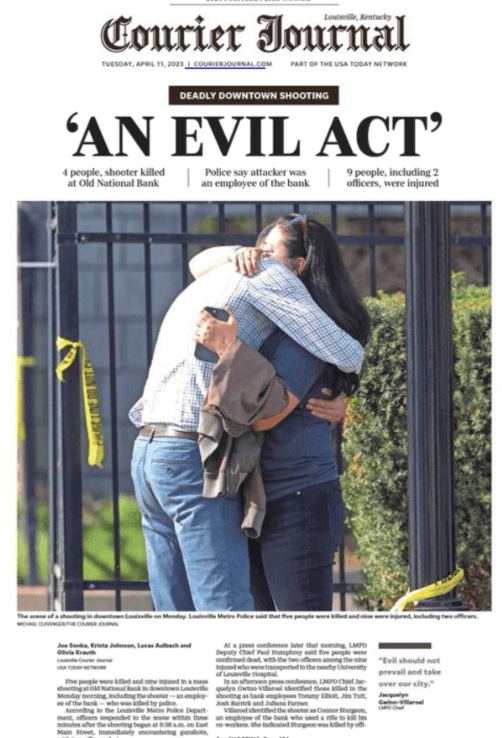

Did you hear about the recent deadly mass shooting at a Louisville bank? According to stories in the media, the killer was a 25-year-old employee. He had worked at the bank for six years, first just in the summers, then full time beginning in 2021. No doubt, he knew most everyone who worked there. Had he been in the Federal civil service, we would say that he had completed probation and was on track to becoming a career employee.

He had a master’s degree in finance from the University of Alabama. Only about 13 percent of the adult population in the U.S. has an advanced degree, so he would be among the more highly educated in most any workforce. He participated in sports in high school.

Apparently, he had raised complaints, perhaps within his workplace. At one point he said, “They won’t listen to words or protests. Let’s see if they hear this.”

So far, there’s nothing unusual about the history of the shooter or the job he held. His description could easily parallel the history of many Federal civil servants: Start your career while young in college, stick to the same type of job for several years, get a good education to prepare yourself for advancement. In fact, that’s exactly how the writer of this article started working for the federal government. Nothing outstanding or exceptional to make this guy stand out.

And then, the twist. He found out that he was about to be fired. As of this writing, we don’t know the reason for that removal decision, but perhaps it was misconduct or unacceptable performance. Soon after, on Monday, April 10, he walked into his workplace with an AR-15 rifle and killed five coworkers, at least two of whom were management officials. He set up an ambush and shot a responding police officer in the head. It is clear he probably would have killed more people if not for the heroic response by law enforcement.

Could this tragedy have been prevented? Could these five innocent lives have been spared? Although there are a number of hypotheticals that could have prevented these killings, the one most relevant to every reader of the FELTG Newsletter is this: Had the employee-shooter been barred from the workplace as soon as the tentative decision to fire him was made, he could not have accessed the workplace with his weapon and his murderous intent. This all happened in a bank, for goodness’ sake, probably one of the most secure workplaces around. Take away his employee hard-pass, instruct security not to let him through the door, and the chances are good he would not have been able to do this terrible thing. I don’t think it takes a great mind to see the advantage to keeping an individual away from the workplace once a tentative decision has been made to fire him. Even good people sometimes make bad decisions.

Now let’s look at the procedures relative to addressing the tentative removal of a Federal employee. Unlike in the private sector, a Federal employee is entitled to three important procedural steps relative here:

- A written notice proposing removal and explaining the reasons for the tentative firing,

- An opportunity to respond, and

- 30 days of pay prior to the implementation of the proposal.

Nothing in law requires an employee be allowed to access the workplace during this 30-day notice period, not even for the response. It is completely consistent with the Federal statute that lays out the removal procedures for a civil servant for the proposal notice to tell the employee that he will be paid for 30 days, but he is barred from the worksite until a final decision is made. Given what happened in the Louisville mass shooting, one might think it prudent to do exactly that. Unfortunately, that is not what the government’s regulations require. Check this out, taken from 5 CFR § 752.404, with my comments in parentheses.

- Under ordinary circumstances, an employee whose removal has been proposed will remain in a duty status in his or her regular position. (That means IN THE WORKPLACE.)

- In the “rare” circumstances in which the agency determines that the employee’s presence in the workplace may pose a threat, the agency may:

- A. Assign the employee to other duties, (Elsewhere in the workplace?)

- B. Allow the employee to take leave (Why would an employee use up accrued leave when there is a legal guarantee of full pay until a decision is made on his proposed removal?), or

- C. Place the employee in a paid leave status, away from the workplace, e.g., bar the employee.

Although these procedures eventually allow the agency to bar the employee from the workplace, they do so only after stating that a barring should “rarely” be done.

As a prerequisite, the agency must somehow make the determination that it would be dangerous for this particular individual to remain at work.

Look back over the brief description of the Louisville shooter. Read more about his background if you can find it on the web. Do you see ANYTHING in his history as it was known to his supervisors that would have led them to conclude that his presence in the workplace might pose a threat? It’s fair to conclude that if the shooter had been a Federal employee whose removal had been proposed, he would have been retained in his regular position, in a Federal workplace, where he would be able to avoid the metal detectors at the entry to the worksite by waiving his employee credentials at the guard.

And if that guy happened to be a coworker of yours, where might you be today?

Folks, here at FELTG, we have big drums, medium-sized drums, and tiny little drums. We beat them on occasion because we have great respect for the good work done by most every Federal employee, and because we believe the civil service is a fair and efficient system for employing the career individuals who run our country. The inexcusable and obvious horrific situation potentially created by these regulations gets our loudest beats from our biggest drum. Why, oh why, these regulations are in place, given the clearly appalling potential outcomes and easy fixes, is simply beyond our understanding.

If you know who can change these regulations, or who can tweak your agency’s own interpretation of these regulations, please implore them to DO SOMETHING. What happened in that workplace in Louisville is going to happen again if we don’t act to stop it. Wiley@FELTG.com

[Editor’s note: The recording of Shana Palmieri’s recent virtual training event Assessing Risk and Taking Action is available for purchase. The session provides guidance on identifying signs of imminent violence, creating a risk assessment team, understanding personality traits and cognitive issues, responding to threats or violent acts, and much more. To bring this presentation live to your agency, email info@feltg.com.]