By William Wiley, October 23, 2018

In a previous article, we laid out an alternative dispute resolution mechanism that employees could opt for if offered the option by management. Unlike the traditional ADR process of mediation, this form of ADR requires that the employee waive other rights of redress and resolves the matter permanently at its terminus. We called this procedure an Administrative Jury and promised you a discussion of its pros and cons in a later article. Well, this is that later article.

Instead of a pro/con approach, we’ll analyze the Administrative Jury option from a love/hate approach. These days if you watch cable TV, you will recognize that love/hate has become a very standard way of viewing life these days.

Lovers – There are some groups that are going to love Administrative Juries as an option to the standard redress systems:

- Employees who want a prompt resolution to workplace disputes. Employees who believe that they have been mistreated will opt for juries to get a quick day in court. Sometimes employees believe that the whole management structure in an agency is a coven of witches and devils. By giving the employee a chance to be heard by a group of coworkers, the grieving employee is bypassing those evil managers and hopefully getting a more neutral, perhaps even employee-biased, decision.

- Managers who want a prompt resolution to workplace disputes. A pending discrimination complaint against a supervisor can adversely affect the supervisor for years. The Sword of Damocles is a good analogy. It’s like a splinter in your foot until you finally get it out. No more coerced mediation or constructive apologies. No more depositions and responding to document demands. No more being cross-examined by someone trained to make you look like a racist idiot. You get in, you make your best case, and you rest easy and early knowing that you’re going to win more jury decisions than you’re going to lose.

- Employees and managers who don’t want to spend a lot of money. Years ago, GAO estimated that the cost to the government of an MSPB appeal was about $100,000 IF the removal was upheld. Senior counsel in a big DC law firm can charge above $800 per hour to represent an individual in a complaint or appeal. For some higher ups, that’s not a lot of money, but it is for those lower in the pay scales, the ones that need the help the most.

- Why coworkers? Because an Administrative Jury is the ultimate in “employee engagement.” Give employees the chance to help decide who gets to work at the agency and you have empowered them to have a significant impact on their daily lives. No longer are they just on the receiving end of whatever it is management wants. You are treating them as adults who have a joint responsibility with management to make the organization function as it’s supposed to function.

Haters – There are other groups who stand to take advantage of the current system and would not want to see anything replace it:

- Private sector employment lawyers, the ones who make a good living representing employees in the traditional redress systems. They provide a service in which their income is based on how long it takes them to provide counsel to a client. They can still have an income in an Administrative Jury system, but it’s not going to provide enough income to buy a new Tesla every year.

- Attorneys on both sides who believe that their side is always right, and if they just do enough discovery, examine enough witnesses, and file scintillating briefs written mostly in Latin, they will be victorious. These folks do not subscribe to the old maximum, “Don’t let the perfect defeat the good enough.” They demand that every rock be overturned and will take a case all the way to the Supreme Court to prove to the rest of the world that they are the smartest, more righteous litigant in the case. They cannot accept that a system that produces a good-enough answer quickly can be better for America than a system that produces the “right” answer every time.

- Employees and managers who believe that they need to punish the other side by dragging it through traditional litigation. Tell me you don’t know employees who intentionally file baseless complaints to coerce management into something, and I will tell you that you haven’t had much experience in this business. Fortunately, these folks are the exception, but they still exist. And they would never opt for a quick resolution via the jury route when they can cause great suffering and pain through traditional redress procedures. They don’t want an answer, they want a fight.

So, there you have it. In three brief articles, a system that could improve the civil service greatly. Hopefully someday someone in a position of power will give this approach a trial. That someone could be you. Pick a component of your organization and set up this option. Try it for a year or so. Have a neutral third party evaluate the results. Then tell the rest of the world how it worked out. Did you know that some of the high-tech companies out here in Silicon Valley near where I work give an award every quarter to the internal organizations who try something outside the box, and fail? They see the value in trying something new even though there is a chance for failure.

If you’re happy with the EEO complaint system we have now, if you look forward to being attacked at an MSPB hearing, if you have nothing better to do in your job other than deal with workplace disputes, then forget these three articles. However, if you believe that there just might be a batter way to run the government, here’s your procedure and now’s your chance. Be brave. Grab the gold ring. And most of all, have fun doing something new. Wiley@FELTG.com

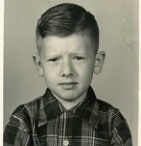

I’ve always been a worrier. Even in my class picture from the second grade, you can see that I have a lot on my mind and the weight of the world on my shoulders. There are so many rules in life and someone has to be concerned that we all follow them. Even at the ripe old age of seven, I somehow knew that would become my mission in life.

I’ve always been a worrier. Even in my class picture from the second grade, you can see that I have a lot on my mind and the weight of the world on my shoulders. There are so many rules in life and someone has to be concerned that we all follow them. Even at the ripe old age of seven, I somehow knew that would become my mission in life.