While there’s no clear connection between the term “master bedroom” and slavery, the subtext is enough that the real estate industry largely moved to stop using it. Here’s why.

By Deborah J. Hopkins, October 16, 2023

The Merit Systems Protection Board has taken a several-week break from issuing decisions while it updates its e-Appeal online system. The system was scheduled to come back online this week.

In the meantime, I wanted to highlight an interesting recent case involving a supervisor who was demoted for conduct unbecoming, but who the Board reinstated because the supervisor’s impatient and unprofessional demeanor did not rise to the level of actionable misconduct. Glass v. Treasury, NY-0752-19-0200-I-1 (Aug. 16, 2023)(NP).

The appellant, a supervisory national bank examiner, was demoted based on five specifications of conduct unbecoming a supervisor. According to the case, the misconduct involved the supervisor’s interactions with four subordinates and the specifications all related “to the manner in which the appellant dealt with these individuals regarding work-related matters.” Id. at ¶7. The administrative judge (AJ) agreed with the agency and upheld all five specifications and the demotion.

The Board, however, disagreed. Among the relevant details:

Specification 1: The appellant addressed one of his subordinates in a scolding manner, told him his work-related project explanations were “not a good excuse,” and told the subordinate that he was ill-prepared for a meeting. In addition, he called the subordinate a liar during a performance review.

According to the Board, “It is the job of a supervisor to address the performance of his subordinates and the making of inaccurate or false statements about a work-related matter is serious. Although the appellant’s language may have been direct or indelicate, that does not make his conduct actionable.” Id. at ¶9.

According to the Board, “It is the job of a supervisor to address the performance of his subordinates and the making of inaccurate or false statements about a work-related matter is serious. Although the appellant’s language may have been direct or indelicate, that does not make his conduct actionable.” Id. at ¶9.

Specification 2: The appellant was having a discussion with another of his direct reports and was trying to clarify how many work items were pending. When the direct report did not understand the appellant’s question, “the appellant held up one finger from each hand in her face and said, loudly enough so that others could hear, words to the effect of ‘Here’s one finger and here’s one finger. How many fingers?’” in front of several other staff members. Id. at ¶10.

The AJ found this behavior disrespectful and inappropriate because the direct report felt intimidated and embarrassed. The Board disagreed and said the appellant was asking for information about a work-related matter, which is a supervisor’s responsibility, and even if the statement was exaggerated and made the subordinate feel uncomfortable, it did not rise to the level of actionable misconduct.

Specification 3: This specification involved the same direct report from Specification 2, above. In this instance the direct report asked the appellant a question about a work-related matter and the appellant responded, “We have talked about this five times!” Id. at ¶12.The AJ found that the appellant’s obvious annoyance and anger was not tactful and was unbecoming a supervisor, but the Board disagreed because the conversation was about “a work-related matter and his response to her was in the context of his supervisory role…To the extent that the appellant’s response reflected that he was frustrated by the question, it does not amount to actionable misconduct.” Id. at ¶13.

Specification 4: The appellant asked a different subordinate to schedule a meeting to include him and two other agency officials, and after the subordinate made several attempts to confirm the appellant’s attendance, he replied, “I told you this three times. We have to go over this again?” Id. at ¶14. As in Specification 3, the Board held that the discussion was work-related and the appellant was acting within the scope of his responsibilities, and even if he appeared annoyed and made his subordinate feel belittled, it did not rise to the level of actionable misconduct.

Specification 5: In an email exchange between the appellant and one of his direct reports, he told her to “submit her questions either to him or another named individual, and to ‘PLEASE stop emailing’” another agency employee. Id. at ¶16. The AJ found the tone of the email unprofessional, but the Board disagreed. It held a supervisor has authority and responsibility to “direct who should be provided certain information and to whom questions should be addressed. Putting a written word in all capital letters is generally intended to draw the reader’s attention to it.” Id. at ¶17. Although the subordinate testified she felt “beaten up” by the email, according to the Board “those feelings cannot serve to turn the appellant’s email into actionable misconduct.” Id.

If you are surprised by this outcome, let me draw your attention to a footnote where the Board explained, “We do not suggest that a supervisor’s conduct may never be actionable and therefore supportive of discipline, but only that the appellant’s conduct in this case does not rise to that level.” Id. at p. 7. For more on advanced topics such as these join us for the all-new program Advanced MSPB Law: Navigating Complex Issues, October 31 – November 2. Hopkins@FELTG.com

By Ann Boehm, October 16, 2023

While teaching a recent class about hostile work environment, a participant asked me if an offensive bumper sticker on a co-worker’s car could create a hostile work environment.

Hmmmm. Interesting question.

Let’s work through this, shall we?

First, what is a hostile work environment? To establish a hostile work environment, an employee has to show that: “(1) he belongs to the statutorily protected class; (2) he was subjected to unwelcome conduct related to his membership in that class; (3) the harassment complained of was based on [the protected status]; (4) the harassment had the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with his work performance and/or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment; and (5) there is a basis for imputing liability to the employer.” Xavier P. v. Patrick R. Donahue, Postmaster General, EEOC Appeal No. 0120132144 (Nov. 1, 2013).

[Editor’s note: Hostile work environment is one of the challenging topics that will be covered during Advanced EEO: Navigating Complex Issues on Nov. 15-16 from 1-4:30 pm ET each day. Register now for one or both days of training.]

Next, is a picture or symbol something that can create a hostile work environment? According to the above-cited Xavier P. case, the answer to that question is most certainly, “yes.” What created the HWE in that case? “Caucasian employees in [the employee’s] work area wore t-shirts featuring the Confederate flag several times a month, and management took no action despite receiving complaints about it.” Id. The union president informed the postmaster that some employees found the t-shirts offensive and asked management to take action to prohibit the t-shirts in the workplace. The postmaster had a subordinate supervisor tell employees “not to wear revealing clothing or clothing with ‘political’ messages.” Id. The employees “were never instructed not to wear or display images of the Confederate flag.” Id.

Next, is a picture or symbol something that can create a hostile work environment? According to the above-cited Xavier P. case, the answer to that question is most certainly, “yes.” What created the HWE in that case? “Caucasian employees in [the employee’s] work area wore t-shirts featuring the Confederate flag several times a month, and management took no action despite receiving complaints about it.” Id. The union president informed the postmaster that some employees found the t-shirts offensive and asked management to take action to prohibit the t-shirts in the workplace. The postmaster had a subordinate supervisor tell employees “not to wear revealing clothing or clothing with ‘political’ messages.” Id. The employees “were never instructed not to wear or display images of the Confederate flag.” Id.

The EEOC concluded the t-shirts subjected the employee to unlawful racial harassment. It also found the agency liable for not taking appropriate corrective action to stop the harassment. If wearing a Confederate flag t-shirt in the workplace constitutes racial harassment, could that carry over into the parking lot? I think so, but I did not find much guidance in case law on bumper stickers. I did find one EEOC “bumper sticker” case. Lockwood v. John E. Potter, Postmaster General, EEOC Appeal No. 0120101633 (2010). The employee did not claim HWE, only discrimination based on race and sex after seeing a bumper sticker in the office trash can that said, “When All Else Fails Blame The White Male.”

The bumper sticker was removed from the trash can, and it eventually was placed on the complainant’s personal vehicle – but not while the car was parked on agency property. (Can we all agree that the facts of this case are just plain weird? Who puts a bumper sticker, particularly one that could be offensive, on someone else’s personal vehicle?) The EEOC found no discrimination because the complainant “failed to show how the alleged incidents resulted in a personal harm or loss regarding a term, condition, or privilege of his employment.” Id.

So, what about an offensive bumper sticker on a personal vehicle parked on agency property? Sorry to do this. I have to give a lawyerly answer here. It depends. The EEOC told us that a Confederate flag in the workplace was racial harassment. Logically, that could cross over into an agency parking lot. Things that could impact on creating a hostile work environment: location of the parking lot (do people have to pass the car?; is it a small parking lot with few cars or large parking garage with many floors?); whether certain employees have assigned parking spaces (the union president or senior officials – knowing who is displaying the bumper sticker could make a difference); and the particular symbol on the bumper sticker (Confederate flag; sexually suggestive pictures or phrases). Would a bumper sticker of a skeleton hand extending a middle finger create a hostile work environment? (Yep, I drove onto a government facility behind that one.) Offensive, perhaps. Hostile work environment, probably not. Hard to say that one is tied to any particular protected status. What’s an agency to do? Employees have a right not to be subjected to a hostile work environment. Offensive symbols or pictures can create a hostile work environment.

There is the potential for a bumper sticker to create a hostile work environment. It all comes down to a fair analysis of the totality of the circumstances in light of the legal standard. The big takeaway from all of this – take a complaint about an offensive bumper sticker seriously. Instead of telling you that’s Good News, like I usually do with this article, I’m just going to say: Good luck out there! Boehm@FELTG.com

By Dan Gephart, October 16, 2023

By Dan Gephart, October 16, 2023

Sen. Joni Ernst is clearly not a fan of remote work. She recently accused Federal teleworkers of “fraud.” Dig beyond the headline and you’ll see many of Ernst’s claims were based on outdated reports. But she may have been onto something when she asked how many Feds were still getting location-based pay and Washington, D.C., wages while teleworking from elsewhere.

We now know of at least one remote worker whose actions fit that description. And while those actions were not outright fraudulent, they did show a lack of candor, according to a recent initial decision by a Merit Systems Protection Board administrative judge (AJ). In Atterole v. VA, PH-0714-23-0184-I-1 (Sept. 7, 2023)(ID), the Veterans Benefits Administration removed the appellant for failure to follow the agency’s telework policy and lack of candor.

The appellant’s duty station was Baltimore. In the early days of the pandemic, she (like most of her Federal colleagues) was granted 100 percent telework. In December 2020, citing the deaths of her mother and brother-in-law, she requested to work from Port Charlotte, Fla. She said she’d work in Florida from Jan. 4 through March 4, 2021, and return sooner if needed.

The VA Telework policy did not require employees to change their duty station when they are working outside of their geographic region for fewer than six months and their absence is related to medical or other personal reasons. However, the employee was still working and living in Florida seven months later.

She failed to provide a Baltimore address to leadership and didn’t update her telework agreement – violations of agency policy.

Meanwhile, the VBA, concerned about allegations that employees were living in states other than their duty station of record and improperly receiving locality pay, appointed an investigatory board. And the employee’s sworn testimony before that board made matters worse.

At first, the appellant invoked her Fifth Amendment right, then stated that she had “permission to be in a different state but that’s all I’m going to say on the matter.” She also told investigators that “there was no expiration, [that she was] waiting on stuff to handle some personal matters …,” before testifying that other people on the staff were working from different locations than their geographical region. When asked to identify those people, she admitted that she knew of no one else beyond herself.

The AJ noted that while lack of candor doesn’t require intent to deceive, an “element of deception must be demonstrated,” and, in this case, the appellant knowingly gave “evasive and incomplete answers … with the intent to mislead the agency.”

The employee countered that the agency failed to reasonably accommodate her disability and retaliated against her for that activity. Her request to work from home 100 percent of the time was denied. However, the agency granted her numerous accommodations including a light above her desk, a space heater, stand-up desk, ergonomic chair, designated parking space and, in the event her office temperature couldn’t be regulated, the option to work from home temporarily. When the pandemic hit, she was granted 100 percent telework.

The AJ found the employee’s “vague assertions” failed to show by a preponderance of evidence that the EEO activity was either a motivating factor in or a but-for cause of her removal. The AJ concluded that the deciding official properly considered the relevant Douglas factors and found removal to be an appropriate and reasonable penalty. Gephart@FELTG.com

By Frank Ferreri, October 17, 2023

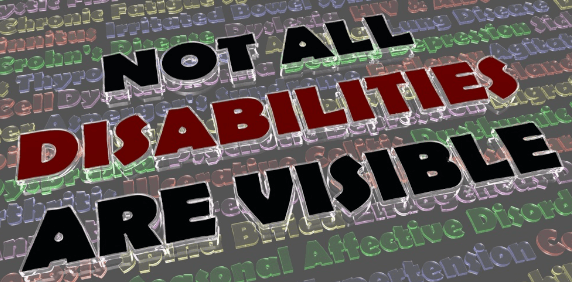

Although the Rehabilitation Act just turned 50, and the ADA is in its 30-something stage of life, employers – Federal and otherwise – continue to struggle with accommodations, particularly for employees whose disabilities aren’t visible.

A couple of weeks back, Fortune ran a story reporting that only 41 percent of neurodivergent employees said they received a workplace accommodation, with another 6.5 percent saying they were denied accommodations after requesting them.

In the context of Federal employment, the recent case of Harp v. Garland, 2023 WL 6380019 (W.D. Okla. September 29, 2023), provides an example of an agency failing to follow the law on accommodating an employee with an invisible disability.

According to a Department of Justice employee, the agency violated Section 501 of the Rehabilitation Act when it denied her request for a reasonable accommodation.

The employee alleged she asked the agency for two hours off work each week to attend therapy for her mental health condition. In response, the agency contended that the employee was able to perform the essential functions of her job without an accommodation.

At trial, the jury returned a verdict in the employee’s favor and awarded her compensatory damages of $250,000.

At trial, the jury returned a verdict in the employee’s favor and awarded her compensatory damages of $250,000.

The DOJ entered a Post-Trial Motion for Judgment as a Matter of Law (Note: Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a party can file this kind of motion within 28 days after entry of judgment, and a court may: 1) allow judgment on the verdict; 2) order a new trial; or 3) direct the entry of judgment as a matter of law.)

To show that an agency came up short in its accommodation responsibilities under the Rehab Act, an employee must show:

- She had a disability.

- She was an otherwise qualified individual.

- She requested a plausibly reasonable accommodation from the agency for her disability.

- The agency failed to provide her with her requested accommodation or any other reasonable accommodation.

Although it noted the employee performed her job duties “adequately” immediately following the denial of her request for an accommodation, in upholding the trial court’s ruling in the employee’s favor, the District Court highlighted that:

- The employee testified that in the absence of her treatment, her mental state deteriorated to the point that she was unable to work.

- The employee testified that she believed the denial of her requests to attend her counseling sessions caused her to be unable to work and that, if she had been able to continue her treatment, her mental condition would have improved.

“Viewing this evidence in the light most favorable to [the employee,] a reasonable jury could have concluded that allowing [the employee] to take leave to attend counseling sessions was an accommodation that would have enabled [the employee] to perform the essential functions of her job,” the District Court wrote.

So, what can an agency learn from a case like this? It’s no secret there has been a mental health crisis in workplaces across the country for a while and that since the pandemic, the numbers have shown it’s not going away anytime soon.

Rather than end up in court or dealing with the EEOC, a better strategy might be to hone in on the tips FELTG Training Director Dan Gephart offered in the thick of the pandemic:

- Develop clear expectations and agreed upon solutions to meet the goals and expectations of the job.

- Communicate in a clear and concise manner, especially the policies and procedures that may impact their performance.

- Provide respectful, but direct feedback. Also, ask the employee how they prefer to receive the feedback.

- Avoid judgments or assumptions.

- Avoid using language that promotes stigma.

Also, as this case illustrates, just because the employee can get a job done “adequately” doesn’t end the story.

The employee’s condition deteriorated without the accommodation, something that most employers would be sensitive to regarding a visible, physical impairment.

It sounds basic, but it’s worth remembering that the law doesn’t make a difference between physical or mental disabilities when it comes to employers’ accommodation duties.

If an employee needs time off to attend mental health counseling sessions, there’s a good case that it will be a request for reasonable accommodation under the Rehabilitation Act, and an agency would make a smart bet to treat it as such. Info@FELTG.com

In recent years, employees have been more open about their faith in the workplace, much of this trend fueled by a number of religious-themed Supreme Court decisions. We’re taking a deeper look.

A high-profile situation naturally raises an oft-asked question about consent as it relates to voluntariness and unwelcomeness in workplace relationships. Read more.

By Deborah J. Hopkins, September 11, 2023

The Merit Systems Protection Board holds a number of functions; chief among them is reviewing agency penalty selections in cases of appealable discipline. The Board’s role is not to displace management’s responsibility in a penalty determination with its own, but to determine whether management exercised its judgment and issued a penalty within the tolerable limits of reasonableness. Alaniz v. U.S. Postal Service, 100 M.S.P.R. 105, ¶ 14 (2005). The same is true of the role of MSPB administrative judges (AJs).

In reviewing recent nonprecedential cases, I noticed several where the Board reversed an AJ’s mitigation and re-imposed the agency’s initial removal penalty. What follows are summaries of two such cases.

The FBI Special Agent Who Fired His Service Weapon

on a Would-Be Car Thief

From a window on the second floor of his home, an FBI special agent saw a man attempting to break into his wife’s car in front of his home. The agent yelled at the would-be thief to get him to stop, but the man persisted. The agent then brandished his service weapon, identified himself as a law enforcement officer, and fired one round, injuring the individual.

At the time he fired his weapon, the appellant was approximately 10 to 25 feet higher than the individual, and 30 feet horizontal distance from the individual.

The agency removed the appellant. On appeal, the AJ mitigated the removal to a 60-day suspension, finding the agency improperly considered certain Douglas factors to be aggravating. The Board disagreed with the AJ and reinstated the agency’s removal penalty, relying on three aggravating factors:

- The appellant’s refusal to accept responsibility,

- The appellant’s prior disciplinary history, and

- The appellant’s “refusal to cooperate with the investigations.”

In addition, the Board agreed with the agency that the misconduct was “directly related to the agency’s mission and the appellant’s ability to exercise reasonable use of force in the performance of his duties in the future.” Kalicharan v. DOJ, NY-0752-16-0167-I-4 (Jul. 20, 2023).

The Disrespectful VA Practical Nurse

The agency removed the appellant, a practical nurse for the VA, based on three charges. On appeal the administrative judge found the agency proved only one charge, inappropriate language, with two specifications:

- While the appellant was in the breakroom with a male coworker, a female coworker called that individual on the telephone and the appellant “yelled out something along the lines of kill that b-tch.”

- During a meeting with management regarding the appellant’s alleged interpersonal conflicts with the female coworker, he admitted to calling the coworker a “b-tch” on one unspecified occasion after she had allegedly lied about him acting inappropriately towards her.

The AJ mitigated the penalty of removal to a 30-day suspension largely because she sustained what she considered to be only the “least serious” of the initial three charges. In explaining the mitigation, the AJ “focused on the context in which the appellant used the inappropriate language and the appellant’s past discipline.” The deciding official considered these to be aggravating factors, but the AJ disagreed.

The Board overturned the AJ’s mitigation and reinstated the removal, after considering as aggravating factors “the appellant’s work in a healthcare setting with veterans, the high standard of conduct and behavior towards patients and other VA employees expected of an individual in the appellant’s position, and the notoriety of the offense in negatively affecting the trust of veterans and the public in the level of patient care at the VA.”

Also, this was the appellant’s third disciplinary offense in less than three years. Therefore, using the principles of progressive discipline, the Board found removal did not exceed the bounds of reasonableness. Beasley v. VA, CH-0752-17-0273-I-1 (Jul. 19, 2023).

We’ll be looking in more detail at these topics during our brand-new virtual training Advanced MSPB Law: Navigating Complex Issues, October 31 – November 2. We hope you can join us! Hopkins@FELTG.com

By Ann Boehm, September 11, 2023

By Ann Boehm, September 11, 2023

Have you heard about the newest anti-discrimination law? On Dec. 29, 2022, President Biden signed the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA) into law. It’s the first new anti-discrimination statute since 2008. It went into effect on June 27, 2023.

What is it exactly? The PWFA recognizes that there are gaps in the Federal legal protections for workers affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions, even though they may have certain rights under existing civil rights laws (gaps in Title VII, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, ADA, and FMLA). 42 U.S.C. § 2000gg. The PWFA allows workers with uncomplicated pregnancies to seek accommodations, recognizing that even uncomplicated pregnancies may create limitations for workers.

[Editor’s note: Join us on Nov. 14 for Up to the Minute: The Latest Changes to Reasonable Accommodation for Pregnancy, Disability, and Religion.]

Agencies violate the PWFA if they do not make reasonable accommodations to the known limitations related to the pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions of a qualified employee, unless the agency can demonstrate that the accommodation would impose an undue hardship on the agency’s operation. Sounds a lot like reasonable accommodation under the Americans with Disabilities Act, right?

Yes! That’s precisely the goal of the PWFA. It acknowledges that a pregnancy without complications is not a disability under the ADA, but any pregnancy still might require some reasonable accommodation. And let’s be honest here. Unless your employee is an elephant (elephants have the longest gestation period of any mammal), it’s usually a short-term accommodation.

What would be examples of the PWFA reasonable accommodations? Schedule changes; telework; parking spaces closer to the entrance; light duty; additional breaks, especially in more physically taxing positions; modifying the work environment; removing a marginal function such as climbing ladders or moving boxes; modifying uniforms or equipment; and adjusting exams or policies that require physical exertion.

Of course, there could be more options. It’s an interactive process – just like the ADA.

Truth be told, most agencies are probably already doing these things for pregnant employees. The EEOC has long held that an employee temporarily unable to perform the functions of her job because of a pregnancy-related condition must be treated in the same manner as other employees similar in their ability or inability to work. This new law should not require substantial adjustment in how the government does business.

As I often say with any request for a reasonable accommodation – treat the employee requesting it like a human being. The agency’s mission must be accomplished, but supervisors should figure out a way to accommodate a pregnant employee’s needs for the limited time the accommodations are needed. It’s always been a good idea. And now it’s the law. For so many reasons, that’s Good News. Boehm@FELTG.com

By Dan Gephart, September 11, 2023

The overworn idiom about the road to a certain scorching and undesirable place (no, I’m not talking my former state of residence, Florida) being “paved with good intentions” applies to the Rehabilitation Act. Just replace the H, the E, and both hockey sticks with an even spookier term — compensatory damages.

In Complainant v. GSA, EEOC Appeal No. 0120083575 (2009), that amounted to $3,000.

The lesson of Complainant v. GSA is this: When it comes to medical records or any information about an employee’s medical condition, you must remember the information is confidential. It should not be shared except in limited prescribed circumstances – and good intentions is not one of those circumstances.

The employee, who had multiple disabilities, had moved between jobs while working for the agency over a decade. When one job ended due to lack of work, the employee was transferred to a warehouse facility. Instead of reporting to the new workplace location, she applied for the agency’s voluntary leave program.

The employee, who had multiple disabilities, had moved between jobs while working for the agency over a decade. When one job ended due to lack of work, the employee was transferred to a warehouse facility. Instead of reporting to the new workplace location, she applied for the agency’s voluntary leave program.

Her application contained a certification from her doctor stating that she suffered from “panic disorder without agoraphobia, adjustment disorder unspecified, and occupational problems.” The application also noted that the complainant had a negative sick leave balance of 231.7 hours and had used 240 hours of advanced sick leave.

The employee’s request for voluntary leave was approved.

Everyone is happy. Great solution. End of story, right? Umm, not so fast.

While soliciting voluntary leave donations for the employee, her supervisor emailed coworkers and happened to mention the employee suffered from PTSD/anxiety disorder “with” agoraphobia.

As a result, the employee experienced a drastic increase in insomnia, anxiety, stress, major depression, emotional distress, shame, loss of self-esteem, and radical weight fluctuations. It’s more powerful in her own words:

I was at least able to hide my mental conditions before my diagnosis was publicly released. After my diagnosis was released, I suffered nausea and pain in my stomach for several weeks. My head hurt me constantly. I was too depressed and ashamed to leave my home unless it was for something that was absolutely necessary such as to buy food or other necessities. I tried to hide when I was in public for fear of running into someone that saw the email. The subject e-mail was even forwarded outside of the agency.

There was not a widespread email in Becki P. v. Dep’t of Transportation, EEOC No. 0720180004 (2018). Nor was there any mention of a specific disability. Yet, the results were similar.

A supervisor had a heated discussion with an employee. After the employee left, the supervisor tried to explain the employee’s behavior to a contract employee who had witnessed it. The supervisor told the contractor the employee is “on medication.”

This, FELTG Nation, is a per se violation of the Rehabilitation Act.

Once again, the disclosure caused distress for the employee with a disability. In the employee’s words:

It became known around the office that I was on mental medication and my symptoms-psychological and physical-worsened. I felt greatly embarrassed and I was deprived of my dignity. I felt even greater distress and sadness, fell into a deeper depression, and became more withdrawn.

The AJ awarded the employee $1,000. Upon review, the commission determined an award of $2,000 was more consistent with awards in similar cases.

It’s important to note that there were multiple claims in each of these cases, and yet the only finding of discrimination in both was for the inappropriate disclosure of medical information.

Join us next week (Sept. 18-22) for Absence, Leave Abuse & Medical Issues Week where leave, medical records, confidentiality, and more will be discussed. Click here for the day-by-day description and register here for one day, all five days, or anything in between. Gephart@FELTG.com