By Dan Gephart, October 17, 2018

Author J.K. Rowling wrote in one of those boy wizard books: “First impressions can work wonders.” Well, they didn’t work wonders for J.K. Her first Harry Potter book was rejected by 12 different publishers before it found a home and became an industry all its own.

First impressions aren’t to be emphatically embraced, but tempered with caution.

Exhibit A: Gritty.

The Philadelphia Flyers of the National Hockey League introduced Gritty as their new mascot on a recent Monday morning. What stands out on the seven-foot-tall mound of unkempt orange fur is the set of googly eyes that never blink. Media called Gritty a big orange blob, a creep, terrifying nightmare fuel, a cross between Elmo and Grimace gone wrong, the Babadook of professional sports, and the most frightening mascot ever invented. There was widely held agreement that he had a major substance abuse problem.

Gritty was the laughingstock of social media. Within a few hours of his introduction, he was photoshopped into images from every horror movie imaginable. People shared videos showing their young children screaming at the sight of Gritty’s monstrosity.

As morning moved into afternoon, it became clear: The Flyers had made a miscalculation of epic proportions. Gritty was the New Coke of mascots. The Flyers haven’t won a Stanley Cup since Jimmy Hoffa disappeared. Maybe Gritty needed to vanish, too.

But then the unexpected happened. People started to embrace Gritty. Perhaps, the mascot’s human side came out when he slipped on the ice during his first night on the job. Or maybe people felt bad about the abuse he was taking. Maybe people liked the resiliency Gritty showed as he got pummeled all over the Internet. Whatever it was, fans (most, not all) got over their shocking first impressions.

First impressions are formed within milliseconds and based heavily on our biases. I sometimes get mistrustful when someone offers me a limp handshake or fails to look me in the eyes when greeting me. I have to regularly remind myself: There are many reasons why someone may not have a firm handshake or may look down at the ground when we meet. It could be ability-related, or there could be cultural or religious reasons.

All hiring managers are trained at some point to avoid the “Just Like Me Complex.” Whether we admit it or not, we are biased in favor of people like us, whether it’s our race, gender, political beliefs, education, or personality. You are all aware of the study that found that resumes bearing African American or Hispanic names received half as many callbacks as those with more traditional white names.

First impressions lead to untold poor hiring decisions every day. Let the job candidate worry about that first impression. You need to make a decision that isn’t based on that initial gut feeling. Here are some ways to avoid the first impression trap:

- Self-identify your biases and be aware of the role they play when making personnel decisions.

- Focus on the objective, job-related qualification standards of the position for which you’re hiring.

- Ask the same questions of all candidates. (While you’re at it, make sure to leave out any questions that border on illegality.)

- Take careful notes during each interview. The notes will help you make the best decisions. They will also help protect you if there is a future discrimination claim.

If you’re unsure of any of these suggestions, well get yourself some training. As you know, we offer that training – and we do it quite well.

By the way, Gritty’s week got much better after that rough start. There were appearances on Good Morning America and the Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon. In a sports world overrun with forgettable sports mascots, Gritty appears here to stay.

May you see the true Gritty in your next hire. Gephart@FELTG.com

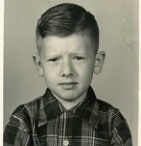

I’ve always been a worrier. Even in my class picture from the second grade, you can see that I have a lot on my mind and the weight of the world on my shoulders. There are so many rules in life and someone has to be concerned that we all follow them. Even at the ripe old age of seven, I somehow knew that would become my mission in life.

I’ve always been a worrier. Even in my class picture from the second grade, you can see that I have a lot on my mind and the weight of the world on my shoulders. There are so many rules in life and someone has to be concerned that we all follow them. Even at the ripe old age of seven, I somehow knew that would become my mission in life.