By William Wiley, March 13, 2019

Way back in the early ’80s, when I was just a GS-12 ER puppy working for Navy, a brand new MSPB board member named Dennis Devaney spoke at a conference I had helped pull together. In his speech, he announced that the Board was about to issue a decision that would hold that if an employee was having performance problems, the relatively new Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 required that they be dealt with through the relatively new Chapter 43-PIP procedures rather than through the old school adverse action procedures. This issue had been hanging out there since 1978, with OPM providing advice that it was mandatory that agencies use the Chapter 43 procedures and avoid the Chapter 75 adverse action procedures when confronted with bad performance.

Even at that limited-experience point in my career, I already knew that was going to be a bad decision. I recently had been advising a supervisor about a pediatric nurse who was engaging in such bad performance that she was perhaps on the road to killing patients. She failed to give medications if the patient didn’t want to take it. She did not keep an eye on IV needles, thereby ignoring any that had perforated the vein and were infusing fluid into the surrounding tissue. When I asked OPM for advice, the response was that I had to PIP her and could not fire her using adverse action procedures. When I asked how many dead babies I should consider to be an indicator of unacceptable performance, they told me to assign one of my spare nurses to follow her around all day to make sure that didn’t happen. Like I got a closet full of spare RNs. Geez Louise.

Member Devaney and I happened to run into each other the evening after his speech (in the hotel’s bar, of course; I LIKE BEER!). Failing to have the good graces vested in a frog, I confronted Member Devaney about the idiocy of his pending decision, the one that would require that poor performers be given 30 PIP days or so to commit even greater harm to the government. Mr. Devaney graciously ignored my youthful arrogance, thanked me for my opinion, and that was that.

Several weeks later, I got a letter from Mr. Devaney. This is before email, children, a time when adults communicated using paper, ink and stamps. In his note, Dennis described how the more he thought about our discussion, the more he appreciated the problem that would be caused by mandating Chapter 43-PIP procedures for all performance problems. When he returned to his office from the conference, he discussed the issue with the other two Board members, and they decided NOT to limit agencies to using just PIPs when dealing with a poor performer. The decision recognized that since the beginning of our civil service, agencies had been able to use adverse action procedures to fire poor performers, and nothing in the Civil Service Reform Act did away with that option. That principle is still good law. When confronted with a poor performer, supervisors are not limited to Chapter 43 procedures and are free to use discipline/adverse action procedures whenever they see fit. In fact, the Board’s case law is chock-full of removal actions taken under Chapter 75 that are based on bad performance.

Unfortunately, that word didn’t get around very well. For example, maybe a dozen years after that decision, I was dealing with an OSC investigator/attorney. The agency I was representing had reassigned a poor performer to another position in which it thought the employee might succeed. The attorney from OSC argued with me that such a reassignment was illegal, that the employee was entitled to be PIPed instead. Holy moly. Am I the only one who has read the Board’s decisions? And has a smidgen of common sense?

That brings us to today; 35 years deep into Board case law. So, what do I see coming out of EEOC and echoed by some others who opine in this field? This:

“Work product errors and untimely completion of work assignments are not matters of misconduct; they are matters of performance.” EEOC reasoned that “measures designed to address performance problems, such as appraisals, remedial training, non-disciplinary counseling, and Performance Improvement Plans (PIPs)” be used. Marx H., Complainant, v. Richard V. Spencer, Secretary, Department of the Navy, Agency, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission-OFO Appeal No. 0120162333, Agency No. 14-00259-03453 (June 19, 2018)

EEOC appears to be saying that using adverse action procedures for bad performance is somehow “improper.” Well, that was an issue back in the early 80s. But it was resolved back then, and is just as wrong today as when OPM advised me to assign backup nurses to keep a PIPed coworker from harming babies and small children. When it comes to dealing with a poor performer, there are a number of tools available to the supervisor. With all due respect, EEOC should be making decisions based on the answers provided by case law, not what they think the answer should be. In any particular case, using a disciplinary or Chapter 75-type approach vs. using a “performance improvement” type of approach may be the more reasonable way to go, but both approaches remain available.

What does that have to do with my personal career? At the end of Mr. Devaney’s note, he told me that if I ever wanted to move to DC, he could use someone with front-line practical experience as an advisor on his staff.

I was loading the U-Haul before the week was out, heading off to a career that gave me a chance to see civil service law from the inside out. And, what’s the professional-development lesson in here for all you youngsters out there?

Drink beer. Wiley@FELTG.com

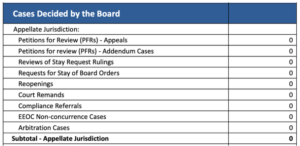

If you’ve been in the federal employment law arena for more than five minutes, or if you’ve read this newsletter in the recent past, you know that we (the People) have been without a quorum at MSPB for more than two years now. In fact, next Friday marks the end of Mark Robbins’ tenure as the sole remaining Board member, at which time the MSPB will have ZERO members for the first time in its 40-year history.

If you’ve been in the federal employment law arena for more than five minutes, or if you’ve read this newsletter in the recent past, you know that we (the People) have been without a quorum at MSPB for more than two years now. In fact, next Friday marks the end of Mark Robbins’ tenure as the sole remaining Board member, at which time the MSPB will have ZERO members for the first time in its 40-year history.