By Deborah J. Hopkins, February 14, 2023

It took less than a year of a quorum at the MSPB before we got our first two cases involving agency discipline related to COVID-19 – consequently, both from the Air Force. In one case, the agency prevailed. In the other, the Board mitigated the appellant’s removal to a seven-day suspension. Let’s take a look.

Opposed to Wearing a Mask

The appellant was a GS-06 pharmacy technician whose job duties included filling and refilling prescriptions, entering orders into a medical database, checking medication stock, inspecting the pharmacy, and consulting with patients and physicians. In March 2020, the agency imposed a mask mandate for anyone entering the medical center, including employees. The agency stationed personnel at the building’s entry to enforce its mask policy, and to screen would-be entrants for fever. Once inside the facility, employees were permitted to remove their masks if they were able to keep physically distanced from other people.

In September 2020, the appellant was stopped twice at the entryway for not wearing a mask. The appellant subsequently informed agency officials she had “a sincerely held religious belief that precluded her from wearing a mask or other face covering.” In November 2020, the agency imposed a more stringent mask policy, which required individuals in the building to be masked at all times unless they were alone in a room and behind closed doors. The next day, the appellant was told that if she did not wear a face covering, she would not be able to enter the building and report for duty.

The appellant contacted the EEO office and “began to absent herself from work in order to avoid the mask requirement.” She exhausted her leave and remained absent from work for several weeks. In January 2021, the agency proposed her removal for (1) unauthorized absence and (2) failure to comply with established leave procedures. The removal was implemented in April 2021.

In her appeal of the removal, the appellant alleged affirmative defenses of religious discrimination and EEO reprisal. The AJ held – and the Board affirmed – the appellant did not prove her affirmative defenses: “[A]lthough the appellant’s religious beliefs, her refusal to wear a mask, and the absences underlying her removal are linked, a finding that the appellant was removed for either unauthorized absences or failure to follow masking policy does not entail a finding that the removal was motivated by the appellant’s religious beliefs.”

The case includes a discussion of the agency’s exhaustive efforts to consider a religious accommodation, and it’s worth a read if you have any role in processing (or defending against) religious accommodation requests. In the end the Board sustained the removal. Davis v. USAF, DA-0752-21-0227-I-1 (Feb. 2, 2023)(NP).

Fabricating Wife’s COVID-19 Diagnosis

The appellant in this case was a WG-10 composite/plastic fabricator. On April 28, 2021, he reported to the agency his daughter was exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19. The next day, he reported his daughter had tested positive for COVID-19, so the agency ordered him to stay home for 14 days.

The day before he was scheduled to return to work, he reported that his wife had just tested positive for COVID-19. He was ordered to stay home an additional 14 days. He finally returned to work on May 27, and “later submitted to the agency photos of two COVID-19 home testing kits, appearing to have positive results, with his wife and daughter’s names written on the test cards.”

On June 10, the appellant’s friend called the agency and requested a day of LWOP for the appellant because he “ was incoherent due to medications he was taking.” The agency, concerned for the appellant, requested the police perform a wellness check.

The police found the appellant wasn’t home. After the wellness check, the appellant’s second-level supervisor called the appellant’s wife to inquire further. The appellant’s wife stated her daughter had an exposure to COVID-19 at school but that “[n]o other Covid incidents happened,” which contradicted the appellant’s version of April events.

Over the next several days, the appellant was absent from work multiple times. He provided a note from a chiropractor to cover the absences. His supervisor, suspicious about the authenticity of the notes, called the medical office to confirm. The supervisor learned the appellant had not seen the chiropractor on at least two dates for which he provided medical notes. Also, he was not given a note excusing him from work.

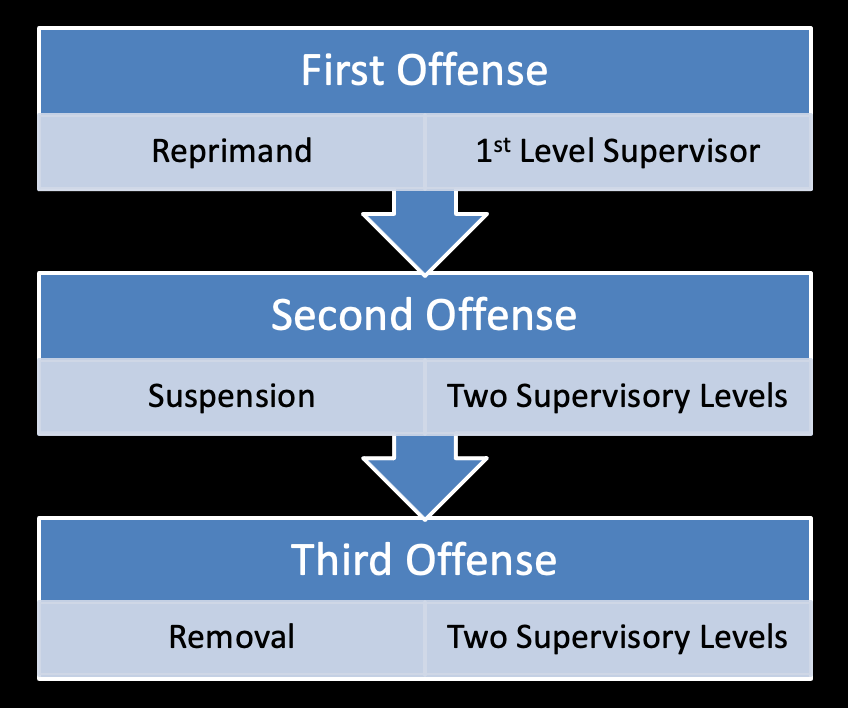

As a result, the agency proposed removal, with three charges: (1) lack of candor; (2) disregard of directive; and (3) unauthorized absence. The deciding official sustained all three charges. The appellant filed a Board appeal but did not request a hearing, so the AJ issued an initial decision based on the written record, sustaining charges 1 and 2 but not charge 3. The AJ also denied the affirmative defenses of disability discrimination under the theories of disparate treatment and failure to accommodate. The AJ upheld the removal.

On PFR, the Board scrutinized the credibility of the evidence and the witness testimony. The Board held the agency did not prove Lack of Candor because, among other things:

- The statements about COVID-19 made by the appellant’s wife were recounted secondhand by agency officials.

- When the appellant’s wife spoke to agency officials, she was angry about being asked for personal medical information.

- While some of the appellant’s statements are not entirely consistent, “we find that as a whole, the agency has presented insufficient evidence to prove by preponderant evidence that the appellant’s statements regarding his wife and daughter testing positive for COVID-19 were untruthful.”

- While the appellant has admitted he added an additional date to the medical note, he claimed his doctor authorized him to do so.

- There was conflicting evidence within the chiropractor’s office about whether the appellant was seen on a particular date.

Because all three specifications failed, the agency did not prove Lack of Candor. The Board held the agency proved one specification of Disregard of Directive related to the appellant’s improper leave request procedures.

Because the agency failed to prove Charges 1 and 3 and only proved one specification of Charge 2, the Board found removal to be unreasonable and mitigated the penalty to a 7-day suspension.

The Board’s brief Douglas analysis relied on mitigating factors, including that “the appellant made contact with the agency to inform his supervisor that he would be absent, albeit not in the way in which he was instructed” and that “[the appellant] and his wife were having relationship troubles.” It gives insight into the Board’s reasoning, so it’s worth a look. Ortiz v. USAF, DE-0752-22-0062-I-1 (Jan. 25, 2023)(NP).

While these cases are nonprecedential, they include a number of important takeaways and lessons about the current Board, which we’ll discuss in more detail next month during MSPB Law Week. Join us March 27-31 on Zoom and we’ll fill you in on everything you need to know. Hopkins@FELTG.com

By

By  A recent MSPB nonprecedential decision has me scratching my head, as the outcome appears to go against over 40 years of case precedent. I wrote about the facts of the case in a

A recent MSPB nonprecedential decision has me scratching my head, as the outcome appears to go against over 40 years of case precedent. I wrote about the facts of the case in a  There are always two sides to a reasonable accommodation (RA) case: the agency’s side and the complainant’s side. While a lot of our training programs at FELTG focus on avoiding agency liability, there’s another aspect to this that’s important to mention, and that’s doing the right thing for the employee who requests accommodation. We see too many instances where an agency handles an RA request improperly, and it exacerbates the employee’s medical condition, causing further harm.

There are always two sides to a reasonable accommodation (RA) case: the agency’s side and the complainant’s side. While a lot of our training programs at FELTG focus on avoiding agency liability, there’s another aspect to this that’s important to mention, and that’s doing the right thing for the employee who requests accommodation. We see too many instances where an agency handles an RA request improperly, and it exacerbates the employee’s medical condition, causing further harm. When we discuss tangible employment actions in our

When we discuss tangible employment actions in our

By

By