By Deborah Hopkins, March 14, 2018

There’s yet another recent EEO decision that makes me ask the question, “When it comes to providing reasonable accommodation to an individual with a disability, how far does an agency need to go?”

And the answer, based on this particular case: pretty darn far.

Here’s what happened. The complainant, a management and program analyst for the FBI, had exhibited some attendance issues and so the FBI issued a notice of proposed removal. In response to the notice, the employee disclosed that she suffered from major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder, and those disabilities were the cause of her attendance issues. She asked the FBI for an accommodation that would allow her a flexible amount of time (the language in the case is “daily variable schedule”) to complete her scheduled 80 hours of work per pay period. She even provided medical documentation that said she was “chronically sleep deprived” and a flexible schedule would provide her with a medical benefit.

The FBI supervisor, probably trying to be nice (because there is no legal requirement to cancel proposed discipline after the disclosure of a disability), held the removal in abeyance for 90 days and granted the complainant a “gliding schedule” that would allow her to report to work any time between 8:00 and 9:30 a.m. Despite this accommodation, the complainant was still late for work 21 times during the 90-day period. According to the agency, the complainant blamed several of her late arrivals on child care issues.

So, after the 90 days elapsed, the agency removed the complainant for AWOL and she filed a reasonable accommodation claim and requested a Final Agency Decision. The FAD found that Complainant was not denied a reasonable accommodation, and so she filed an appeal to the Office of Federal Operations.

The EEOC found that the FBI did not grant a reasonable accommodation and remanded the case (5 years later!), citing a few reasons:

- The complainant contacted her supervisor on 18 of the days she was going to be late, and the agency did not consider granting the complainant leave as accommodation for her tardiness in those instances, instead marking her AWOL.

- The child care issues were related to the underlying disability.

- A maximum flexible schedule would have been an effective reasonable accommodation, and the agency did not demonstrate why the complainant needed to arrive to work by 9:30 a.m.

- The agency did not demonstrate that granting a maximum flexible “gliding” schedule would be an undue hardship.

When I read the case, I don’t see anywhere that the employee requested a “maximum gliding schedule” for the agency to consider. She asked for a “daily variable schedule” which it appears the agency offered her, by allowing for a 90-minute window in which to arrive. But what do I know?

Yep. The EEOC said that the complainant’s oversleeping was a result of her disability and the underlying cause of her attendance issues, so therefore she was not AWOL when she didn’t get to work on time and didn’t call in, and the agency should not have expected her to arrive by 9:30 each day. Davina W. v. FBI, EEOC Appeal No. 0120152757 (December 8, 2017). [Editor’s note: The supervisor might have been able to defend his actions in this claim if he had kept notes of the harm that occurred each time the employee was late. That’s something we’ve been teaching for nearly 20 years. Contemporaneously document your reasons for doing something adverse to an employee, especially if it has the potential to show up as an issue in an appeal/complaint.]

I guess that’s what you get for being a nice supervisor and holding a removal in abeyance, huh? Hopkins@FELTG.com

A few days ago, I got an interesting hypothetical question from a long-time FELTG reader, and it was such a good one I thought I’d share it with the rest of you. It’s something I hope is always hypothetical and you never have to deal with in real life. Here we go:

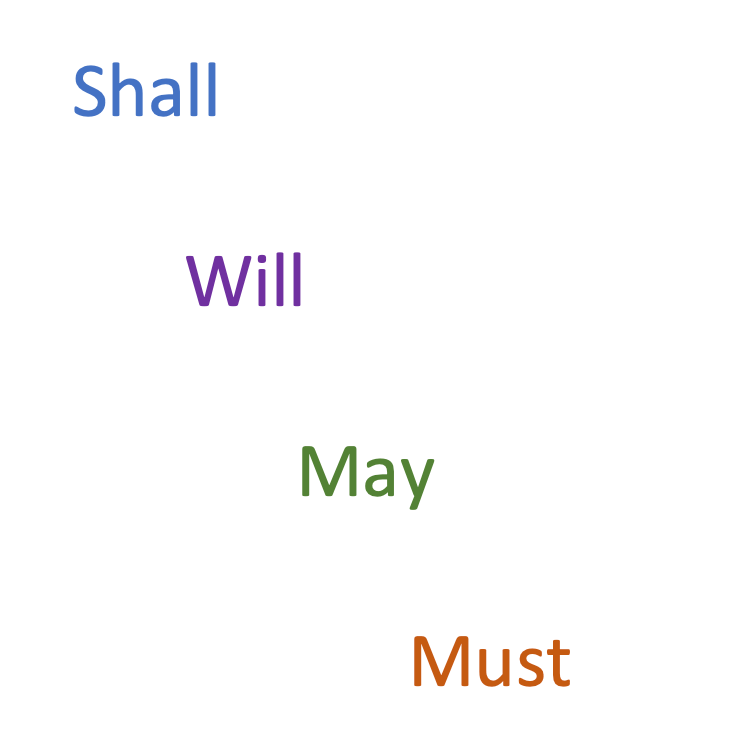

A few days ago, I got an interesting hypothetical question from a long-time FELTG reader, and it was such a good one I thought I’d share it with the rest of you. It’s something I hope is always hypothetical and you never have to deal with in real life. Here we go: The only word of obligation from the list above is must – and therefore, the only term connoting strict prohibition is must not. The interpretation of everything else is up for debate.

The only word of obligation from the list above is must – and therefore, the only term connoting strict prohibition is must not. The interpretation of everything else is up for debate.