By Deborah Hopkins, April 10, 2019

In federal sector employment law, we often use terms of art that carry very specific meaning. These terms may vary from a typical dictionary definition, or even from a black-letter law definition. Examples include discipline, due process, notice, response, representative, supervisor, and even employee.

In federal sector employment law, we often use terms of art that carry very specific meaning. These terms may vary from a typical dictionary definition, or even from a black-letter law definition. Examples include discipline, due process, notice, response, representative, supervisor, and even employee.

A term of art that I want to highlight today is ex parte. This is a Latin term used in legal proceedings meaning “from one party.” The Legal Dictionary definition goes a little deeper: “An ex parte judicial proceeding is conducted for the benefit of only one party. Ex parte may also describe contact with a person represented by an attorney, outside the presence of the attorney.”

That’s fine, but still not entirely helpful for the purposes of agency discipline and performance actions in the federal government. It needs some context. But before the context, let’s do a quick review of the required steps to taking a disciplinary or performance action:

- The Proposing Official (PO) gives the employee a proposal notice which includes the reasons for the proposed discipline (charges; Douglas factors) or performance removal (incidents of unacceptable performance during the PIP), and any relevant supporting documentation.

- The employee responds orally and/or in writing to the Deciding Official (DO), based on the information given in the proposal notice and any other information the employee thinks is relevant. The employee has the right to be represented in this response.

- The Deciding Official makes a decision based ONLY on what is contained in the proposal packet and what was contained in the employee’s response.

These are the due process steps required by law, for any Title 5 or Title 42 career employee who has satisfied the probationary period. So, where exactly does this ex parte concept fit in? Well, there are two primary types of ex parte violations that might arise:

- An ex parte act occurs when an adjudicator considers evidence not available to one or more of the parties.

- An ex parte discussion is one held by an adjudicator without allowing all of the parties to the controversy to be present.

The DO is a management official in the agency and as such makes decisions for the agency, she is also acting as the judge, because she is weighing the evidence to determine what penalty to dole out.

The employee legally is entitled to know all the reasons the PO relied upon, at the time he issues the proposal notice. So an ex parte violation occurs when, after the proposal is issued, the DO becomes aware of new information about the employee or the case, and the employee (and the representative, if he has one) is not made aware of the new information.

Let’s apply this scenario to the two types of ex parte violations above:

- Ex parte act: A coworker of Ed Employee, whose removal has been proposed, sends an email to the DO, informing her that the Ed has been sending inappropriate text messages to her for months, even though she’s asked him to stop. The coworker attaches a PDF with copies of the purported text messages.

- Ex parte discussion: The deputy director of the division sets up a meeting to talk with the DO about the risks of keeping Ed around, when there are unsubstantiated but potentially serious allegations of harassment against him. Ed is never told about this discussion.

Now you can see where the term ex parte comes in – only one side (the DO) gets the information, either intentionally or unintentionally, and Ed Employee does not have a chance to respond to it, because that new information was not in the proposal notice.

If such a violation occurs and the employee finds out about it, then it’s an automatic loser of a case for the agency – even if there is video evidence of the employee committing the charged act of misconduct, 15 sworn statements from credible witnesses, and a confession from the employee himself. It’s a procedural due process violation and that employee cannot be removed or otherwise disciplined.

One of the foundational ex parte cases involved a DOD employee who claimed credit for time not worked on six different days, and was removed for submitting false claims. After the proposal was issued, the Commanding Officer engaged in surveillance of the employee and provided this information, along with additional documents, to the DO – and the employee was not given any of this information. Due process violation, and we’re done; employee gets his job back. Sullivan v. Navy, 720 F.2d 1266 (Fed. Cir. 1983).

Additional cases show that ex parte information, whether it is relied upon or not, automatically violates due process. See Ward v. USPS, 634 F.3d 1274 (Fed. Cir. 2011); Buchanan v. USPS, DA-0752-12-0008-I-1 (2013); Kelly v. Agriculture, 225 Fed. Appx. 880 (Fed. Cir. 2007); Gray v. Department of Defense, 116 MSPR 461 (June 17, 2011). Be careful when doing legal research, though, because you will find cases where agencies got lucky and successfully argued that the new information was not considered, or did not influence the DO. See, e.g., Blank v. Army, 247 F.3d 1225 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (After receiving the employee’s response to the proposed termination, the DO conducted a further inquiry into the matter but there was no due process violation because the interviews only clarified and confirmed what was already in the record.).

You don’t want to hope to get lucky in one of these cases, though. Fortunately there’s a simple fix for an ex parte conundrum, and it will save your case. The DO can simply notify the employee of the new information and give the employee an opportunity to respond to it, before the DO makes a final decision. See Ward, above.

It may bump your timeline back a few days to allow the extra response time, but that’s waaaaaay better than losing a case on a due process violation and having to start from scratch. Hopkins@FELTG.com

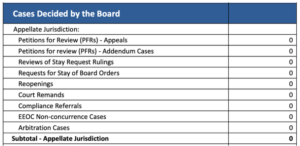

If you’ve been in the federal employment law arena for more than five minutes, or if you’ve read this newsletter in the recent past, you know that we (the People) have been without a quorum at MSPB for more than two years now. In fact, next Friday marks the end of Mark Robbins’ tenure as the sole remaining Board member, at which time the MSPB will have ZERO members for the first time in its 40-year history.

If you’ve been in the federal employment law arena for more than five minutes, or if you’ve read this newsletter in the recent past, you know that we (the People) have been without a quorum at MSPB for more than two years now. In fact, next Friday marks the end of Mark Robbins’ tenure as the sole remaining Board member, at which time the MSPB will have ZERO members for the first time in its 40-year history.