By William Wiley, October 2, 2018

As I watched the Ford-Kavanaugh Supreme Court Justice nominee hearings recently, I was struck by the lack of standards for the process. In case you’ve been in a cave for the past week, the issue of the hearings was whether nominee Kavanaugh had engaged in sexual misconduct with Dr. Ford when they were both teenagers some 35 years ago.

The scene was riveting. Dr. Ford testified consistently and fearfully for five hours as to her memory of a party at which Brett Kavanaugh tried to sexually assault her. Nominee Kavanaugh testified loudly and angrily about how unfair the nomination process had become. Dr. Ford swore that she was 100% certain that the attack occurred as she had described it. Judge Kavanaugh swore that it did not. A classic he-said she-said situation.

Subsequent to the two testimonies, the Senators and media pundits were flummoxed, emotional, and all over the place as to what to do. Who was telling the truth? Where’s the proof either way? THERE IS NO PROOF! OH, YES THERE IS!! Such anger, hostility, and bewilderment as to what really happened that night. Geez, you’d think that the future of America was at stake or something in what is really just a personnel matter.

The more I heard the Smart People talk, the more it became clear to me that our civil service system is designed to determine the truth much better than what the members of the committee and the public commentators are doing.

First, there’s the matter of exactly what does “proof” mean? That concept was thrown around a lot, and it certainly is the heart of the matter. But if you listened closely, you came to realize that there was no generally accepted definition of the concept of proof applicable to the event at issue at the hearing.

Those readers who have attended our civil service law seminars know that there are three levels of proof applicable in personnel matters in the executive branch:

Preponderant Evidence. This is the burden of proof most commonly used in personnel situations because the most common personnel situations involve discipline and discrimination matters. In these sorts of cases, the agency or the employee prove their case if they can show that “it is likely” that the claims are valid; e.g., it is likely that the employee engaged in the charged misconduct that was the basis for the removal.

Clear and Convincing Evidence. The civil service laws have reserved this highest proof burden in personnel matters for the most beloved group of federal employees: whistleblowers. If an agency fires a whistleblower, it must leave the judge with a “firm belief” that the misconduct occurred, not that it just “probably” occurred as the preponderant level would suggest. The courts have defined this as a “heavy burden.”

Just think what kind of difference it would make in the Ford-Kavanaugh controversy if the Senate would simply decree what the burden of proof was for Dr. Ford’s claims:

- If substantial proof is all that is needed, the White House had better start looking for a replacement nominee. I think that few clear thinkers could deny that the event at the party 35 yeas ago “might’ have happened. Dr. Ford’s memory seems burned into her brain, graphic in detail, and consistent in description. No, we can’t say that for sure it happened, but that is not the evidence standard when we say that the proof expectation is only substantial.

- If clear and convincing proof is necessary, Nominee Kavanaugh can start getting fitted for a nicer robe. Some of us might really want to believe Dr. Ford out of compassion for her situation and deep sympathy for someone who has so obviously been traumatized. But aside from those feelings, to my read it is difficult to say that the objective evidence has satisfied the “heavy burden” requirement.

- If preponderant proof is necessary, then we have to decide who is telling the truth: Ford or Kavanaugh.

And, of course, there’s the rub. Senator after Senator, talking head after talking head, has whined and bemoaned that Dr. Ford cannot be believed because there is no corroborating evidence. It’s just her word against his. In the mind of the uninitiated, without corroborating evidence, we cannot have proof at the preponderant level.

MSPB had a similar problem back in its earliest years as an adjudicating body. A number of cases arose in which the removal on appeal hinged on a determination as to which of two witnesses was telling the truth. Some of the Board’s judges (“presiding officials,” back in the day), tried to dodge the bullet by ruling that as they could not determine who was telling the truth, the preponderant evidence level had not been reached. Well, the Board members would have none of that. They reminded the judges that they were being paid to conclude who was being truthful and who was not. So, they remanded those cases to the bullet-dodging judges and told them to do their jobs of adjudicating. In doing so, the Board created a tool that the Senators could very well use today to make the credibility call between Ford and Kavanaugh.

We’ll describe and apply that tool in a later article. We will no doubt be too late to help with this particular nomination, but maybe the next time something like this comes along, the more clear-headed Senators will find it more useful than gut-based truth-determination. Wiley@FELTG.com

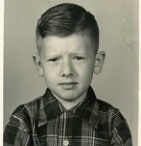

I’ve always been a worrier. Even in my class picture from the second grade, you can see that I have a lot on my mind and the weight of the world on my shoulders. There are so many rules in life and someone has to be concerned that we all follow them. Even at the ripe old age of seven, I somehow knew that would become my mission in life.

I’ve always been a worrier. Even in my class picture from the second grade, you can see that I have a lot on my mind and the weight of the world on my shoulders. There are so many rules in life and someone has to be concerned that we all follow them. Even at the ripe old age of seven, I somehow knew that would become my mission in life.