By Deborah Hopkins, April 23, 2019

One thing I don’t understand is why people make their jobs (and as a result, their lives) more difficult than necessary. Aren’t the challenges that are out of our control already causing enough problems?

In my adventures traveling the country conducting federal employment law training, I’ve come across some suggestions that employment law practitioners offer as advice, that make things far more difficult than necessary for all parties involved. Not all advisors commit these sins; many do not. But in order to make the list, the Deadly Sin has to have been seen in multiple agencies, multiple times over the past year.

Here they are, with my bulleted responses following each:

- Inaccuracy. Advisors in L/ER or OGC tell supervisors they need a three- to six-month record of poor performance before they can put an employee on a PIP/ODAP/DP, or whatever the agency calls the period where the employee is given an opportunity to demonstrate acceptable performance.

- That’s just wrong, and it’s bad advice. As soon as a supervisor can articulate why the employee’s performance is unacceptable, she can put the employee on a demonstration period, as long as the employee has been on her performance standards for a warm-up period of 60 days or so. The only thing that matters in a performance-based removal is what happens during the demonstration period. As long as the reason why the performance action was initiated was not illegal (e.g., based on race or sex or whistleblower status) and the performance is unacceptable now, the employee’s performance before that articulation of unacceptable performance has no bearing.

- Imprudence. There are some jobs that are so high-level, an employee needs more than 30 days to demonstrate acceptable performance; therefore, the demonstration period should be at least 60-90 days.

- No can do. The MSPB has never found a 30-day demonstration period to be too short, regardless of an appellant’s job level or type. Even if the employee’s typical work cycle takes months or even years, there must be some amount of work the supervisor expects to be done within the next month or so. Break the projects down into smaller steps and you’ll find you have a nice 30-day demonstration period. If my suggestion isn’t enough, you may want to note that several agency policies, and even the President in Executive Order 13839, now say that 30-day demonstration period is sufficient. Unless you have a union contract that says you have to provide more than 30 days, you don’t. And you shouldn’t.

- Waste. If an employee fails the PIP/ODAP/DP before the end date, the agency should let the employee finish out the 30-day demonstration period anyway.

- This makes no sense – and could actually cause a lot of harm. Picture this: a TSA security screener who is on a demonstration period, lets a bunch of cocaine and guns get on an airplane in the first couple of weeks of the demonstration period, and you’re going to let that screener continue working for the next several days? If so, I guess you think letting drugs and loaded weapons onto a plane are no big deal. Or what about the nurse who is putting patients’ lives in danger – you’re really going to let him continue to provide poor care after he shows you he cannot do the job acceptably? The same principle applies across the board, no matter the job or what the employee’s critical element is called.

It is a waste of time, taxpayer money, and supervisory resources to allow someone who fails an opportunity period before the end date to finish it out, and there is legal authority that says you can end it early due to error rate. See, e.g., Luscri v. Army, 39 MSPR 482 (1989). The primary issue the MSPB will look at is whether the employee was given an opportunity to demonstrate acceptable performance. We know from the case law that even 17 days is enough time for an employee to demonstrate whether he can do the job acceptably. Bare v. HHS, 30 MSPR 684 (1986). The only time you have to allow the full length of the demonstration period to run is if it is required by your collective bargaining agreement.

- Fallacy. If the supervisor saw an employee engage in misconduct, he can’t discipline the employee unless there is additional evidence to support the charge.

- The standard of proof for misconduct is preponderance of the evidence – or substantial evidence if the employee is covered by the new VA law. If a supervisor saw the employee violate a workplace rule, that’s a preponderance of the evidence. 5 CFR 1201.56(c); 5 CFR 1201.4(q). If you have witnesses and video logs, that’s great – but if you don’t then you still have enough evidence. The only exception is if the employee is a whistleblower; in that case you’ll need clear and convincing evidence, so those extra witnesses and videos will come in handy.

- Risk. Don’t use Notice Leave except in extreme circumstances where you have determined an employee is a threat to safety.

- Notice Leave is a paid leave status, created by the Administrative Leave Act of 2016, that allows the agency to send the employee home with no duties after a removal is proposed, for the duration of the 30-day notice period. In order to use Notice Leave the agency simply needs to document why retaining the employee at work jeopardizes a legitimate government interest, that reassignment is not appropriate, and inform the employee in the proposal that she will be placed in this pay status.

Why wouldn’t you use Notice Leave it every time you propose a removal? Congress created this category of leave exclusively for this situation. An employee whose removal is proposed will not do anything constructive during the notice period – and may even cause severe problems in the workplace. Don’t believe me? Come to our Emerging Issues Week class this July where we talk about people becoming violent in the workplace after proposed removals; even though there may be warning signs, you can’t always predict it. Plus, some people become violent with NO warning at all. Don’t gamble with your life or your agency resources. Use the gift called Notice Leave every time, and you won’t have to wonder who will become dangerous in the workplace after you’ve proposed their removal.

- Apathy. It’s too much work to go through with a misconduct or performance action, and the agency will probably just settle the case anyway, so supervisors should ignore conduct and performance issues unless they are especially harmful or egregious.

- I cringe every time I hear something like this. This is completely disempowering to supervisors and just plain wrong. If a supervisor wants to take an action, the role of an advisor is to make the supervisor aware of the options and to point out potential legal issues – not to tell the supervisor to forget it. If a supervisor has reason to hold someone accountable, then we should support that supervisor.

- Avoidance. If an employee has EEO activity pending, the supervisor must hold off on any discipline until the complaint is resolved.

- If I had a dollar for every time I heard this, I could have retired years ago. This statement is completely incorrect. EEO activity is not a shield for employees, though in reality it has become one in many agencies. Supervisors can discipline employees who happen to have EEO complaints pending, as long as the discipline is not motivated by, or because of, the person’s EEO activity. And here’s another note: It often takes between 3-5 years for an EEO complaint to be resolved, so you definitely shouldn’t wait to hold employees accountable.

I hope practitioners can understand why these pieces of advice are so detrimental to supervisors, and impact the efficiency of the government workplace. If there are other deadly sins you’ve heard about, feel free to share them and they may show up in a future article. In the meantime let’s all work together to make the federal government a better place to be employed. Hopkins@FELTG.com

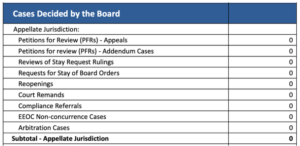

If you’ve been in the federal employment law arena for more than five minutes, or if you’ve read this newsletter in the recent past, you know that we (the People) have been without a quorum at MSPB for more than two years now. In fact, next Friday marks the end of Mark Robbins’ tenure as the sole remaining Board member, at which time the MSPB will have ZERO members for the first time in its 40-year history.

If you’ve been in the federal employment law arena for more than five minutes, or if you’ve read this newsletter in the recent past, you know that we (the People) have been without a quorum at MSPB for more than two years now. In fact, next Friday marks the end of Mark Robbins’ tenure as the sole remaining Board member, at which time the MSPB will have ZERO members for the first time in its 40-year history.