By William Wiley, July 21, 2021

By now you probably have heard that the White House finally has nominated two individuals to be Board members over at the US Merit Systems Protection Board. After more than four years of the civil service having no oversight agency to protect the fundamental rights of federal employees, Cathy Harris and Raymond Limon are now grinding their way through the Senate confirmation process, hopefully to be confirmed sooner than later. Based on my many years working at MSPB, with 12 of the 20 Board members we have had in history, I think I can speculate with some degree of accuracy what awaits them once they get there:

- When I joined the newly confirmed MSPB chairman’s staff in 1993, there were 62 holdover cases awaiting his vote. That felt like a HUGE number of cases to dig through, given that a Board member needs to vote on about five appeals a day just to stay even (i.e., a member who is voting out five cases a day is doing a full day’s work in service to our great country). Our next Board members will be facing a holdover backlog of almost 3500 appeals!

- The Board will have to decide how it will attack this overwhelming backlog. The obvious options would be to address cases first-in/first-out (oldest first), work the removal cases first because they are the most serious matters within MSPB’s jurisdiction, or perhaps try to pinpoint pending cases that have the most significant controversial issues that need to be cleaned up ASAP so their principles can be applied to other cases. Or, quite frankly, any other way the Board decides to plow forward: alphabetical, random, or eeny, meeny, miny, moe. There is no legal standard nor precedence for the new members to look to when deciding how to move forward.

- I say “the Board” because historically big decisions like this would be made through consensus of the sitting Presidentially appointed Board members. However, as a strictly legal matter, the new chair has the sole authority to make decisions like this. During the early days of the new MSPB, the hierarchy of decision-making and comity among the members will have to shake itself out. Although Board members have worked together (with occasional exception) with a respectable degree of deference and cooperation in the past, nothing guarantees that such mutual respect will carry forward into the future. By law, all three members cannot be from the same political party. As I understand it, the current two nominees are Democrats. A third member would no doubt be a Republican, and we’ve all seen what can happen when that happy mix occurs.

Speaking of a Republican appointee, I must admit that I’m unsure what’s happening there. Historically when confronted with multiple vacancies requiring a mix of Democratic and Republican nominees, a White House would seek suggestions from the Senate leadership of the other party for the out-party seats. Then, a package would be put together that incorporated who the White House wanted and who the leadership of the other party wanted into a nice uncontroversial package that would receive a prompt Senate confirmation vote. Has this White House decided not to package? Or is it going to accept an individual already nominated by the past Republican administration for the third vacancy at MSPB? Readers better connected than am I may have picked up on what’s going on, but I haven’t seen it from where I sit.

Aside from these incredibly important matters of Board protocol, each member will be considering several personal matters that are part of being a Board member:

- Staff: MSPB employs a fine headquarters staff of career employment law attorneys. No doubt, some of those career attorneys will be detailed to each new Board member immediately once they take the oath and start considering cases. Beyond that initial period, each member will be allowed to select political appointees to serve as legal counsels, sort of like a federal judge would appoint law clerks. In many agencies, these second-level political appointees would be controlled by the Executive Office of the President or the Office of Personnel Management. A White House often has a long list of political supporters who would just love to have a good government job. However, by law the chair of the Board can make these political appointments without having to get approval from anyone else, 5 USC 1204(j). For those of you readers out there interested in a little career change, we can expect to see the new Board members quickly putting out recruiting feelers.

- Issues: Some newly appointed Board members, especially those with extensive federal law experience, walk in the door with issues they want to address in a new decision with their name on it. Others may have to vote on several cases before they develop a feel of issues that really matter to them. One Board member I worked with had an alcoholic in the family, so he closely reviewed any case involving an alcoholic to make sure that the appellant’s rights were protected. Another member I worked with had represented unions in the private sector and strongly believed in the importance of independent decision-making by arbitrators. Another had grown up in a military family where adherence to rules and order was important. Just like Justices on the Supreme Court, each member will develop a particular interest in some aspect of federal employment law and devote significant time to making sure that issue gets well-analyzed in any final opinions that are issued.

- The next appointment: As is true for just about any Presidential appointment in the executive branch, these jobs come with an expiration date. Although the law provides that a Board member’s term is for seven years, that seven-year period starts on March 1 of a particular year, regardless of when the individual is confirmed to serve in that position. To my knowledge, no one has ever served a full seven years as a Board member. One of the Board member positions to which this White House will be nominating an appointee expires in just about 18 months. So, unless an appointee is at the end of a career, he or she needs to be thinking down the road and working toward the next job. Very few individuals have used an appointment as an MSPB Board member as the steppingstone to an even higher-level government position.

And finally, there will be lots of odds and ends to decide:

- Will the members consider and vote cases remotely, so they never have to come into the office?

- Should the members personally discuss the arguments in the appeals before they are voted on?

- Can the members engage in public outreach by speaking at conferences and seminars, or is their time better spent cloistered in some warehouse reviewing appeal files and reading case law while subsisting on energy drinks, caffeine tablets and meat-lovers pizza?

These new members will have an unprecedented herculean task before them. Although I was honored to serve on the three occasions I was tapped as counsel to a member, I am happy that I have now taken a downgrade into civilian life. I am hopeful that the new members and their staffs enjoy themselves in their service as much as I did. I appreciate the good that they are doing for our country by helping to keep the federal government based on deserved merit and not strictly political philosophy. May the force be with them.

Also, it would be a good idea for them to put a cot and pillow in the corner of their offices. Wiley@FELTG.com

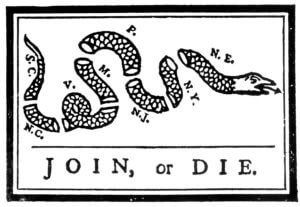

To the left is a flag based on a Benjamin Franklin cartoon published in 1754, urging the eight colonies (all New England is represented as one) to unite.

To the left is a flag based on a Benjamin Franklin cartoon published in 1754, urging the eight colonies (all New England is represented as one) to unite. [Sidenote to that neighbor: Are you lazy or what? That Game 7 loss to the Atlanta Hawks was nearly a month ago. Why must you keep reminding me of that disappointment?]

[Sidenote to that neighbor: Are you lazy or what? That Game 7 loss to the Atlanta Hawks was nearly a month ago. Why must you keep reminding me of that disappointment?] During the video replays of the Insurrection at the Capitol, I saw numerous flags and symbols that I did not recognize, but later

During the video replays of the Insurrection at the Capitol, I saw numerous flags and symbols that I did not recognize, but later